INTERVIEW: Julia Bell on Mentoring and Teaching Memoir

Julia Bell runs the MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck University and was also my supervisor for my PhD. She's been a huge inspiration for me and my writing, and here is a conversation between us

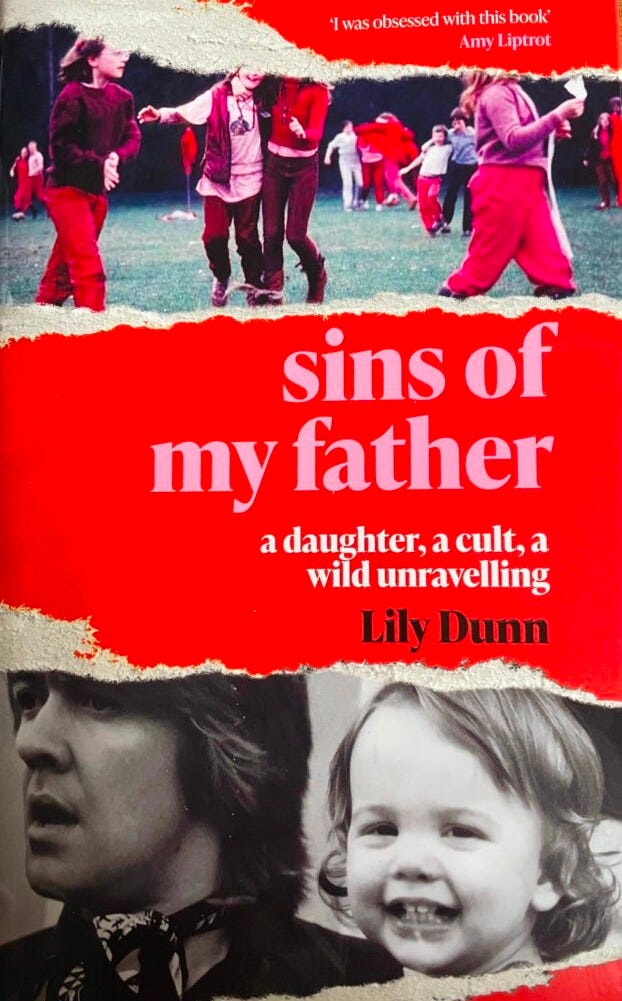

Julia Bell has been an important mentor for me over the years, and, in many ways, she was the main instigator for me to venture into writing memoir. It was with her encouragement that I returned to writing about my father (after writing about him in my first novel, Shadowing the Sun, 2007), which led me to completing Sins of My Father while doing a PhD under Julia’s supervision. Julia is a writer of fiction and creative nonfiction. Her latest book is Hymnal, a memoir in poems, and she is currently putting the finishing touches to a book about teaching, which will be published next year. She also wrote an excellent extended essay on the importance of attention - which I often dip in to still. It’s called Radical Attention and is published by Peninsula Press. This interview between us happened in 2022, and I still return to it to remind me of why I love teaching and mentoring.

Could you define Creative Nonfiction, and tell us a bit about how it is integrated into your teaching at Birkbeck?

Creative Nonfiction is an interesting definition for an incredibly broad range of writing, from a researched project, which might be a history book or a gardening how-to book, to something very lyrical and almost touching the edges of fiction. When I am teaching, firstly the technical aspects of writing are essential for good prose, and that’s essentially time management and development of the persona – the person speaking and telling the story. Those are the two key things we spend most of our time in the classroom thinking about. What I mean by time management, is knowing when to condense time and also when to expand a moment and make something exciting. When to go close in with the focus, and when to draw back. I think this is something readers don’t really think about – they either like what they are reading because they’re immersed in the experience, or they can’t get past the second chapter because they find it too confusing, and there is too much detail – all the research gets in the way. It’s about modulating the pace in which the story is told.

About two thirds of my Creative Nonfiction students are writing memoir, and a third of students want to do something that is researched: maybe they’ve got an interest in a historical moment or know something specific about sport, or they want to write something investigative, which is not necessarily personal. But it still demands the same attention to structure and time management and some of the technical stuff is the same across all those kinds of projects. Whether you’re writing fiction or CNF, we start everyone off with a course on good prose technique, a tool kit: characterisation, structure, point of view.

You’re differentiating between memoir and more research-led writing, but there is a keen interest now in books that combine the two – what are your thoughts on this?

That’s the best kind of CNF because you feel you have a witness in the middle who has experienced some of the things they are writing about. It’s slightly different from investigative journalism where a writer puts themselves deliberately at the centre of a new experience to understand what is going on. This kind of interrogative memoir comes from a writer placing their experience in the broader political and social context. Adam Kay’s This is Going to Hurt is a good example of where you’ve got the frontline experience of the doctor, but you’ve also got the broader experience of working in the NHS in a particular moment, and various bits of information about medical procedures. You go to a book like that not just for the personal insights but also for the knowledge, so it’s an interesting relationship between the two.

Do you think it’s important to bring the personal point of view into straighter narrative nonfiction, ie when the subject is nature writing for instance?

I think it’s much more interesting for the reader if there is a sense of the author’s connection to the subject they’re writing about. There is a big difference between the ghost-written story that is written as if they were the person, and something like Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch, which is much more confessional.

How do you deal with students wanting to write about difficult personal experience?

I tell them the reader is not their therapist, and really they need to go away and process some of the personal stuff before they share it with the reader. It can be rude to expect the workshop group to do that work for you. Of course, as a teacher we need to deal with personal experience sensitively, but I think it’s really important if you are going to publish something that you present it to the reader in a way that is artful. That you treat the reader with respect. You have to process it in order to make the work interesting and that’s part of the process of writing a good piece of memoir. Part of it is self-development.

It’s mostly about getting writers to see that the reader can’t figure out the meaning of what has happened to them without some help. That’s what make the difference. The question we have to ask in the workshop is – what does this mean? This happened to you, and we are sorry about that, but what does it mean in broader society or within your family structure? Or why does it matter to us? In that way the personal becomes political. Vivian Gornick’s theory of the situation and the story is helpful. Quite often people come into class with a lot of information around an incident that has affected their life, but they can’t untangle it to find the story. The workshop helps them turn experience into something with a beginning, middle and end.

A good workshop group also creates an environment where people feel bold enough to share. There is a lot of shame attached to writing, and it’s important for students to know that there is no moral shame in producing a bad sentence.

You have experience mentoring memoirs, and we worked closely together on mine – could you tell us a little about the role the mentor has when working with someone else’s personal content, and how to be sensitive and generative?

Really important to acknowledge and reiterate that good writing is an act of personal development, and it doesn’t come without some painful moments of self-reflection. And that this is not necessarily something that the teacher can help you with. I can say, this is good but there is a gap here, or there’s something missing here, and have you considered what this might mean in relation to that? It’s important to be rigorous without being unpleasant or unkind. This kind of rigour tends to be generative because it involves going off to read a book or think about this thinker, which then creates a new space for the writer to grow into. But the writer needs to do work on themselves, too. Good prose writing is a combination of technique and personal development.

Also, I often tell my students that I can’t teach boring people to be interesting, but I can teach interesting people to write well. Because if you’re innately curious you’ll already be pushing the questions to the next stage. But I can help people to think deeply by showing the kind of questioning you need to do in order for your work to have impact.

Have you ever had students take your feedback the wrong way? If so, how did you manage this?

Some people get upset in the moment, but mostly no, because the workshop group is encouraging and helpful and gets the writer to lean into the things they can do. If someone comes in with poetic prose I’ll get them to lean into that. I think this is important, rather than getting them to write against the grain.

Do you think it takes a certain level of perception to mentor memoir, and particular trust?

With your memoir, Sins of My Father, there was a personal connection, because my sister’s friends moved into your dad’s house in Bolinas after he was deported back to the UK, and there was our shared connection with San Francisco. I also think children of alcoholics and children of religious parents have similar issues. And the more you talked about the story, and the more you lived it, the more it grew. You went from writing essays, to untangle them to extend the narrative into a bigger project, but the story was always there. It was a symbiotic process, us chatting, writing bits, then life happening. It was very satisfying to see how Sins Of My Father came about in that way.

I do also think that the mentor relationship can be therapeutic to a certain extent, although it is not therapy. I was aware with your book that there were other things going on in the background that were aiding your self-development, and they then start to feed into what you’re writing and begin to make it better. I also think writing memoir demands courage, and this again is something that can’t be taught.

Sins Of My Father took many years to write, but then it wasn’t written to commission. How different is it when memoirists have to write to commission and are given a deadline to do it?

Writers like Olivia Laing, who write from commission to commission, seem to get it right. But then her books have developed from the more personally driven Lonely City, so it really depends on what the book is. I don’t think you are going to write another book like Sins Of My Father, so the process would perhaps be a bit easier with the next book, and it would be less about your own personal development and more about the subject. I don’t think you can hit the bullseye with every book.

I am interested in reading witness accounts on how we live now, like Deborah Levy with her living autobiographies. Similar to Annie Ernaux. I love her work for the same reason. People say to me nothing interesting has happened to me, and I say, If you’ve got a curious mind, a short walk across a room is interesting. It becomes about the person who is looking, and the angle from which they look.

Writers might write the first big book, which is the moment of processing the thing that they wanted to write about, and by doing this they also find their voice, their position, their point of view, like Melissa Febos did with Whip Smart. And now what we’re finding in her books is that point of view being deployed to tell me things about her life. So it’s less personal, but the persona is more fixed perhaps. I think there is a process to go through to get to that point. The second book is more about your point of view – your persona.

Could you tell us your opinion on the kinds of memoirs that work, compared to when it might not work?

Ambulance chasing memoirs don’t work – like the Natascha Kampusch book, 3096 Days, about her experience being abducted, held captive in the secret cellar in Austria for eight years. It was published soon after she was saved, but basically written by a journalist. Her story was completely unexpurgated – it was horrible, a victim story, like a statement for the police essentially. And then Emma Donoghue takes that idea and creates art from it with Room. But Natasha’s book came first. I felt prurient reading it, because it was so unprocessed. Compared to something that has been really rigorously thought through – your book is a really good example of that – but other books are Tara Westover’s Educated, or Vivian Gornick’s Fierce Attachments. Here you have an intelligent mind that is able to be nuanced about what has happened to them, not just simply trying to get revenge. I think this is the issue also – what is the purpose of the writer writing this book, why are they telling this story?

I think with Sins of My Father, you had to live it as well as write it. You couldn’t just sit down and synthesise. Life happens in the process of making art. Shit happens. And life affects the art. Maybe more so in memoir than fiction.

Can you give readers any tips if they are writing memoir and are struggling with it?

Ask yourself, why am I writing this story? What is the point of it? Maybe the sticking point is who is the person speaking or what is my time management? Sometimes writers tell everything in the first three paragraphs and then think they have run out of things to say. See if the events can be dug into more deeply than that. Take the reader into the moment and make them sit in that situation with you.